Toward The Cutting Edge: An Interview with Robert Tiemann

Trinity Review, Winter, 1980

Artist Robert Tiemann, for years the artist at TU most concerned with being at the “cutting edge” of modern art innovation, actually didn’t start as an abstractionist painter. Instead, he sort of mutated his arts along a career which began at UT-Austin in the fifties and at USC at Los Angeles in 1960 (a student at both places, he says he doesn’t remember there being a single abstractionist on the faculty of either school at the time.)

At first, he did figurative works. Then, while in LA, he got his first look at abstract art. A show of European abstracts at the LA Country Museum, he says, “wiped me out.” And there was a Miro retrospective going on that took him in its spell. More, he started to get into the local scene—which sure beat anything he’d seen back home in Texas. By the time he’d earned his MFA at USC at LS, he was doing some serious reassessment of what modern art was all about.

He returned to Texas in ’61 and found himself out of touch with what was happening in modern art. Deciding to turn to a personal kind of work, he began imagistic, narrative canvases that had a meaning only he could decipher. At this point, he wanted to create art that wouldn’t refer to what anybody else was doing; that way, he wouldn’t miss the resources and influences that had been within reach during his stay on the West Coast, plus, it would ease the frustration of not being able to keep up with all the important new art getting done in LA (and New York). He got into Chagall, Indian poetry and mythology, and “and a lot of Oriental stuff.” When he arrived at TU in 1965, he remembers, he was still doing fantasy/surreal/Jungian pieces, and telling his students not to pay attention to what they saw in art magazines but to work up their own approach to expression.

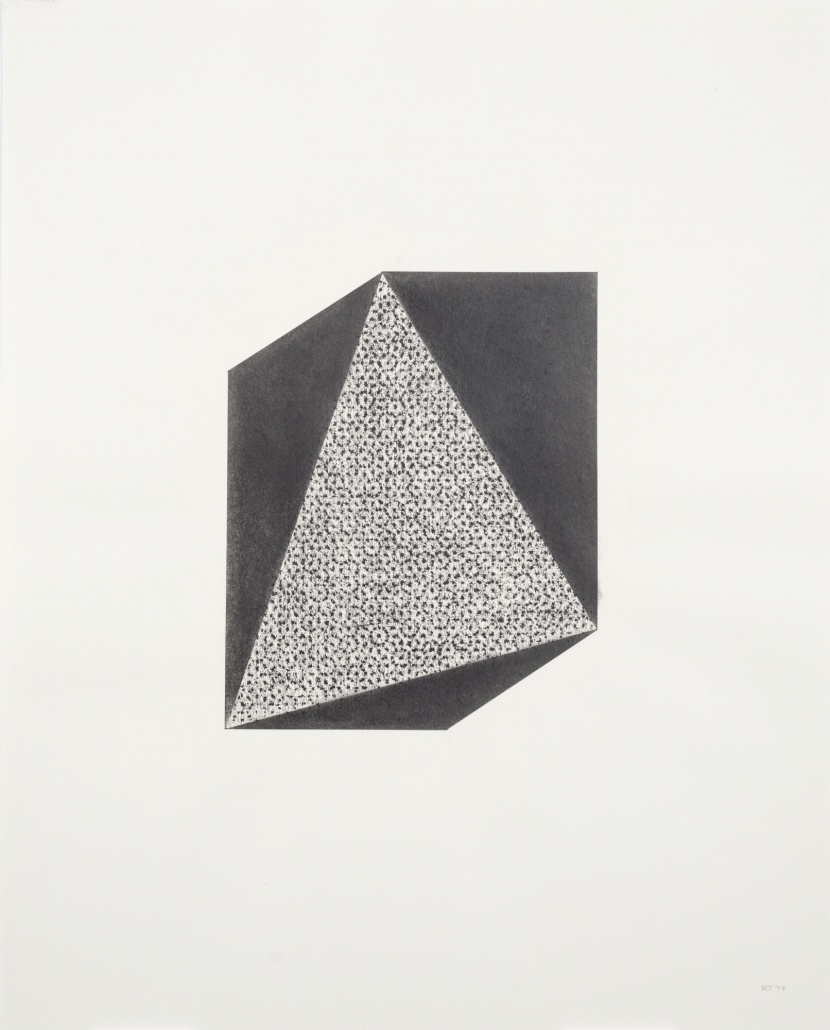

Between 1965 and the early 1970’s, the break came. Tiemann committed himself to the culture of modern art, which demands that the artist, however expressionistic, find new ways to solve problems in composition and, more importantly, discover new problems. He eliminated figures from his painting. At the mercy of chance discovery, he tried pouring paint and various objects on his canvas. Later he stopped mixing colors—and started doing monochrome works with cord gridlines stretched across the canvas, successfully eliminating spatiality from his painting. Finally, his works themselves—constructions of wood and canvas—have taken on aspects of sculpture: three-dimensionality, and identity as a body rather than as a world (existence over essence.) Tiemann hints that soon he may display these latest pieces on the floor, rather than on the wall as he displayed them recently at St. Mary’s University Library.

The following are excerpts from two conversations, taped under the influence of, respectively, Haagen-Daz ice cream and generic beer. We’re hoping it reveals Robert Tiemann the man as well as Robert Tiemann the artist, and we wish him the best of luck during his semester as a guest professor at UTSA this coming spring. Here, then, is Robert Tiemann: RDS

LR: When did you make the transition from subjective, personal art to the objective, concrete art you’re presently involved with?

RT: [In the late sixties to early seventies] I started thinking about making the painting out of its own structure more. I was laying sticks across the canvas and pouring paint around them, thinking the internal structure of the painting would make itself.

The problem with that kind of painting was, I’d do about 15 or so before I got one that worked. And I just figured I needed to work in a fashion that allowed me to have more success.

[In the end] I felt those paintings were too atmospheric. So I decided to eliminate all illusionistic devices from my work. I just sat down one day and made out a list of what I had in my painting and realized I had a lot of contradictions. So I had to make some decisions about what I wanted. One of the things I threw out was color mixture. [In order to eliminate spatiality.] I still think I can work with color but it’ll be in industrial colors.

You won’t believe this but I used to be a real champion of figurative painting but not realistic figure painting. I taught and believed and painted with the idea that you looked at the world and then you sort of colored it with your viewpoint. So I would tell people, “I’m not painting what I see, I’m painting what I feel about what I see.” I would use techniques in my work like Picasso’s sense of distortion, Chagall, Miro. I took courses when I was at USC in German Expressionist art and I was just enthralled with those guys: Max Beckmann, Paul Klee.. I loved that stuff so much.

It just dawned on me one day that a guy with a ruler and a pencil drawing straight lines is just as expressive as a guy who is dripping and pouring paint. I think doing these drawings [indicating a few of his charcoal renderings of a grid, done last winter] is what realy made me understand all that. You can’t say one kind of art is more expressive than another, that just doesn’t hold up. I like to take art out of the realm of the hocus-pocus—you, the “I have this great feeling and it comes out on the canvas” sort of thing that students all come into class with. So now I try to tell them, ‘no, it’s just about being logical; it’s about thinking, it’s about knowing, about intelligence; it’s not about something you’ve got that nobody else’s got.”

LR: You made a statement a few weeks ago that you can only deal with what you can see.

RT: Wittgenstein talks about that and I sort of like the idea. In other words, instead of sitting around talking about metaphysical things like God and love and beauty, thinks that we’ve been asking about for centuries and haven’t gotten any answers for, perhaps we should just talk clearly about concrete things like measurements.

I read Robb-Grillet, the French writer—He deals with facts. …I find it refreshing. Because I have spent so much of my life sitting around talking to people about religion and mystical things and ESP and Zen—ugh, I don’t ever want to talk about Zen again—and all that kind of stuff. And it’s just so nice to talk about [he points to some furniture] that table as a real, concrete table you can bang your shins on. I kind of like the idea of getting things out in the clear light of day. I always admired the Greeks for that. I mean, their gods walked around with them, made love to their women. They weren’t some weird demons that often men were afraid of. I kind of like their clarity. I guess I like classical things. I think it’s really refreshing that 20th century art’s trying to be real objective. I find that exciting. I like the idea of taking the basic skills of a carpenter and just extending them a little bit—not to make them more complicated, but more obvious.

LR: Do you want to talk about your grids?

RT: I’ve been doing the grids [on canvas] since the summer before last. And the drawings were done in January. [The three-dimensional pieces soon followed.]

LR: Do you feel you’ve exhausted the possibilities of working with a two-dimensional form of art?

RT: No…I’ve just gotten interested in something else. You can’t exhaust anything, you can just get bored with it.

LR: So why did you go to three-dimensional art?

RT: My paintings got so flat and nonillusionistic; it seemed to me that the reason you paint on a flat surface that’s a rectangle or a square is because it’s an unobtrusive form, it doesn’t call attention to itself and so it’s a characteristic of realistic painting. So the next question for me was, “why work on a flat surface?”

RS: You’ve said that chance is involved in your work. I’m not sure how, since a lot of what you’re doing these days seems to very controlled, very deliberate.

RT: [Points to a grid drawing of his where, he says, the white spaces inside the grid have occurred completely by chance.]… The more controlled you get, the more you reach a point where some element is almost totally out of control; I don’t know why that is…I think that happens in anything…

You can start out very controlled and the more controlled you start off, the more at some point chaos raises its ugly head. When you get everything honed down to a fine point, then one mistake looks tremendous.

I like for all my pieces, any piece, no matter what kind of work I’m doing, to get to a point where things get critical and then it almost hinges on some lucky happenstance. It’s really a kick to have that happen: to be working on a piece and finally get in trouble with it and then react intuitively. I’ve never been able to do anything where the accidental didn’t come up. It always seems to happen—the more you control something, the more you get it to that point where then when you do screw up or something goes wrong it’s really noticeable.

LR: But you don’t strive for—

RT: I’m not striving for it but it always seems to happen. Everyone thinks that, like Rod said, the grid is my trademark. That’s not really true. I haven’t been doing the grid for very long and I’m probably not going to do it for much longer…I mean, I don’t think the grid is so much a trademark as is getting to the point where the accidental has to come in. I mean, that [the point-of-accident] is more characteristic of all my art.

LR:…Don’t you think that in assigning metaphor to your work that you’re bringing it back, almost regressively, into the classical tradition?

RT: Probably.

LR: Because it’s linguistics. It’s logic, pictorial logic, and actually metaphor brings it [your art] back into the realistic realm.

RT: Anytime we use language, metaphor is going to raise its head. But painting is a metaphor, too. I was thinking about the idea that art is like a parallel world that we build to compare the real world with and I think that’s one of art’s functions. It’s what art does.

LR: Well, that’s been the big issue among people who hated modern art—that it didn’t have an objective language that people could latch onto.

RT: But I think that everybody’s asking that question, that’s why the structuralists are so important. It’s like, we don’t all believe in the same gods; or a god, and so what is the unifying thing in the culture? Maybe it doesn’t exist. Everybody’s looking for it. So the linguists say, “It’s language.” And now we start to find out that’s not really true…So maybe it’s metaphor.

Metaphor’s just another reason for something to exist, rather than just doing something arbitrarily. Michael Graves [the architect] used his color metaphorically rather than arbitrarily:, “well, let’s put a green here cuz it looks nice to put a green here.” Well, that’s another idea, another alternative, and I think it’s worth checking out. So I’ve really started looking at my work along those lines.

.. It may be that paintings are all built on a linguistic system and we don’t know it and structuralist is trying to find that out.

LR: Metaphor as a new language one has to learn?

RT: Or just discover. Realize, the way we’ve discovered the language of the subconscious. Freud and Jung analyzing dreams and discovering that these symbols all have meanings.

RS: On thing that’s interesting to me is the whole idea of impermanent works and also art that is meant to be seen as a reproduction rather than as an original, That all plays hob with traditional role of art history. It’s like, what’s to become of art history? How will we document these…

RT: ….We almost have an art history department—we have a major in it. How about mathematics history? Physical education history? Science history? I mean, why art history?… Why not drama history, music history—I mean have a big department of music history with these guys all going around showing slides of music scores. I think it’s going to change when process gets more widespread, because how do you document process. If you missed a performance you missed the performance, you can’t see it again when it comes to town cuz it’s gonna be different—going to have new actors…if you try to write the history of Hamlet how are you going to do it? So when art becomes more impermanent, the art historian’s going to have trouble.

We didn’t get art history until I guess the 19th century when they started building museums and you had collectors. And the art historian was really there to tell the collector that this stuff he’s paid all this money for was really worth it. So art history created all these categories. And the categories are all based on product. The end product. “This is made out of stone it must be sculpture. This is made out of paint, it must be a painting. And to hell with the process.” What if you changed art history and said, “Let’s categorize things in terms of process?” Painting and ballet might be in the same category.

Art history has always been materialistic…It’s the tool of the connoisseur. Artists don’t need art historians, collectors need them. To tell them why their piece is important. The artist doesn’t need somebody to tell him why his work’s important…or why it’s valuable, cuz he ain’t buying it.

RS: But if it hadn’t been for art history textbooks, it would be harder for students to gain any consciousness of the past to work from. Photographs of classic artworks might be harder to come by.

RT: Well, we’ll probably always have art history. And I’m always pushing the argument too far. I’m not saying we should do away with art history, but I think we ought to reassemble it so that it’s more process-oriented. It makes a lot more sense to me to talk about process than it does final product, “the thing’s made out of clay, therefore it’s sculpture.”

I really believe in modern art. And as Irwin [Robert Irwin, the theorist/environmental artist who visited TU recently] says, modern art is a radical, new kind of art. The basic distinction of this new kind of radical art is: innovation. You’ve got to be innovative, that’s the name of the ballgame. You can’t be a practitioner. Practitioners belong to the old group. There’s no value to a guy painting Mondrians today; maybe in realism you can still paint like Rembrandt, I don’t know. But modern art is based on being on the cutting edge; that the excitement of it. And even if you never get to the cutting edge, it’s sure fun pursuing it. And I’d rather do that than think of myself as some guy trying to keep some time-honored technique alive.